Coen and Nadler would not be where they were in the autumn of 2008—knee-deep in de-classified documents, forensic reports, scribbled notes and interview transcripts; on deadline with a dark film and book about the international biowarfare underworld that encompassed years of globe-trotting, lab-sniffing, interview-begging, and dirty-tricks witnessing; on edge about every new underreported anthrax-related revelation; and far more comfortable with bacterial bombshells than they would perhaps care to be—without the work of Stephen Dresch.

.

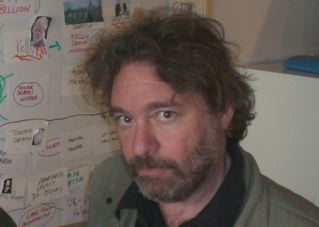

Dresch was an independent investigator—a for-hire sleuth whose constant quarry were corruption, incompetence, professional negligence, and government turpitude. He was an intellectual—a former college dean with an Ivy League doctorate in economics who never rid his speech of academe, even when lowering the boom on mobsters or reading the riot act to high-ranked public servants. A Republican-leaning libertarian from the notoriously independent-minded upper peninsula of Michigan—which he represented in the state legislature for two years in the ’90s before being ousted, he always claimed, by Karl Rove’s operatives—Dresch wore the physical trappings of an iconoclast. By the time he entered Coen and Nadler’s realm, age had bleached his full beard and long hair; years of chain smoking had stained his fingers and teeth. He looked, many would comment, more like the Unabomber than a tireless crime buster who harried the FBI to catch America’s most-wanted. But even in the last years of his life there was an unquenchable youthful light in his eyes—a ray of determination to somehow lessen the badness caused by the overwhelming abundance of malefactors.

.

After receiving a doctorate in economics from Yale in 1975, Dresch went to work at the National Bureau of Economic Research and then to a think tank in Vienna where he would take frequent research trips behind the Iron Curtain His unorthodox career next landed him at Michigan Tech University’s Business and Engineering School in 1985. His five-year tenure as Dean of the school culminated in the ouster of several senior officials who, at Dresch’s instigation, were convicted on criminal charges of corruption. From that point, Dresch’s life became one long search for veracity, progressing from easy-game embezzlement into arenas where the truth, if it ever existed, had gone to die. His final investigative obsession, on which he literally expended his last breath, was anthrax.

.

It would be easy to write off Stephen Dresch, at first blush, as a conspiracy nut. Bob Coen almost did. Any man who knew as much as Dresch did about the comings and goings of Clinton Commerce Secretary Ron Brown, Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols and 1991 World Trade Center terrorist Ramzi Yusuf must be looking for detours between dead ends, he figured. Dresch, Coen would be the first to admit, gave off an aura of mild wackiness. What, after all, is a “high-level forensic economist?” he wondered. And how do you explain the peculiar alter-ego Dresch had apparently invented to hang on his website shingle at “Jhêön & Associates”—one Asphasia Quermut Jhêön, who, in addition to being a truth-seeking sidekick, was also, apparently, a bohemian spirit with deep sources in the Bulgarian and Turkish undergrounds. Together, promised the homepage, Dresch and Asphasia represented “an informal association of individuals dedicated to the principles of liberty and devoted to the exposure and extirpation of corruption.” Informal indeed—it was Dresch who answered all of Jhêön’s emails.

.

But that did not change the fact that Dresch had helped support his wife and four kids by completing assignments for clients spanning from Lloyd’s of London to New York wise guys waging war against the feds’ tough RICO-racketeering statutes. He had proven his chops on more than one occasion, and earned a few headlines. It was his legwork, for example, that helped the Brooklyn District Attorney indict FBI Special Agent Lindley DeVecchio for allegedly assisting a1992 mob hit in Bensonhurst. The sensational charges were later dismissed under unusual circumstances, but not before Dresch’s partner was badly beaten in a parking lot by unknown assailants. And it was his tip that led the FBI to a cache of explosives left by the Oklahoma City bombers, presumably to execute a tenth anniversary attack in 2005. The bureau at first denied finding anything, and then quickly buried details about the cache, which Terry Nichols, serving time for 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Building, had revealed to a fellow inmate (and a Dresch client), along with the news that the explosives were originally provided to Timothy McVeigh’s gang during an FBI-sting gone horribly wrong. Dresch pursued proof of the cover-up with nearly as much vigor as he had applied towards preventing a second act of terrorism.

.

Throughout his gumshoe voyages, Dresch balanced his oddball behavior with a very strict work ethic. For all his talk of “extirpation” and discoveries of “serious mal-, mis-, and nonfeasance within the system of criminal justice,” Dresch was a factfinder, not a brainstormer. He cast a wide net for the dots he would connect, but once he did, Dresch was more intent on drawing subpoenas than conclusions. “I resist becoming an inveterate ‘conspiracy theorist,’” he once wrote to Coen, discouraging his initiate from attributing specific motives to one or more players in their anthrax drama. “The answer may be as simple as . . . sloth, indifference, narrow self-interest.”

.

It was a convoluted path that led Dresch from Oklahoma City to Fort Detrick and secret germ labs abroad. But he wasn’t surprised when it passed close to his own home. Because what he labeled “the international bioweapons mafia,”—a mob he considered the biggest threat to humanity in the twenty-first century—had first come to his attention in the Upper Peninsula Michigan landscape. For Stephen Dresch, the case began with a company called BioPort.

.